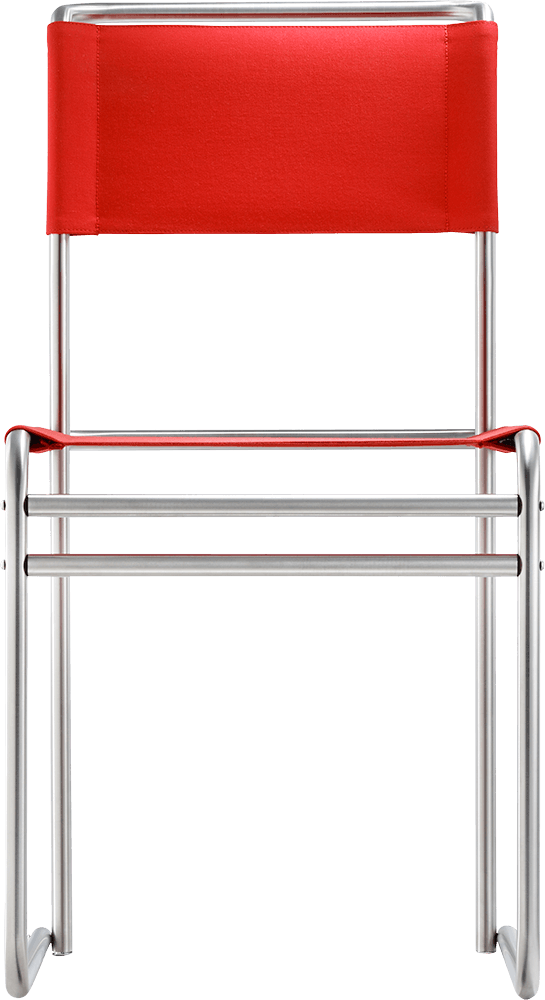

D40

A good chair for a good table

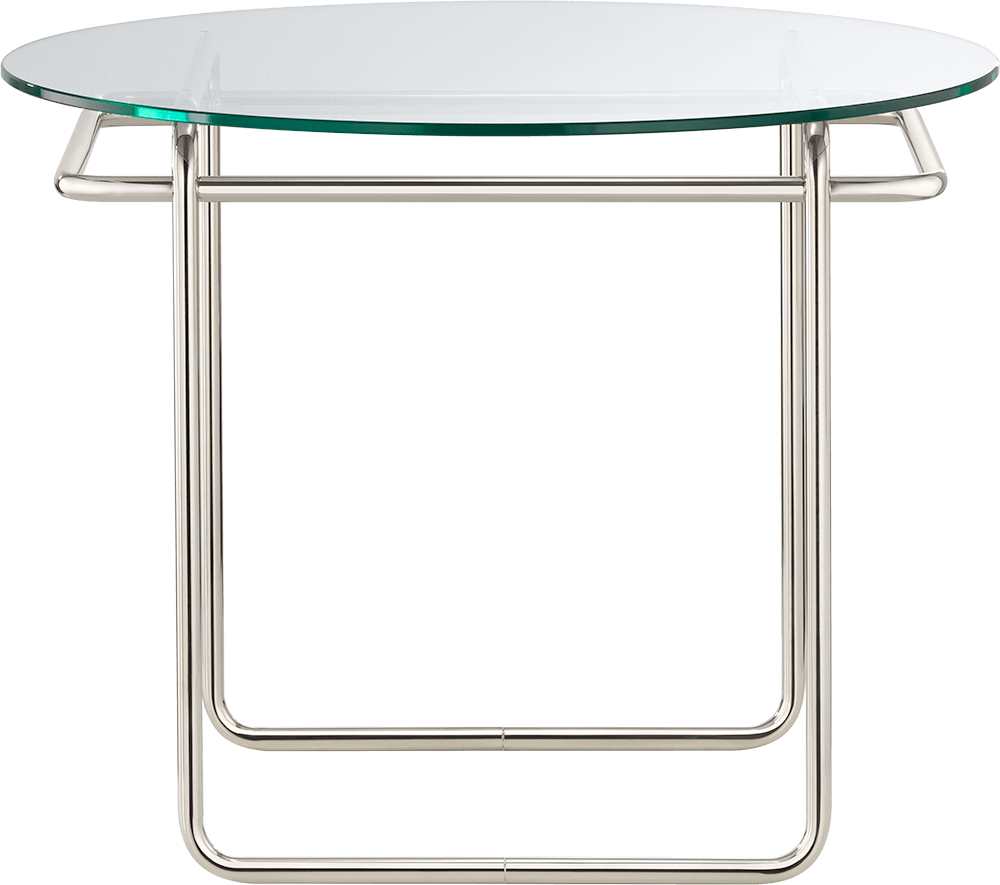

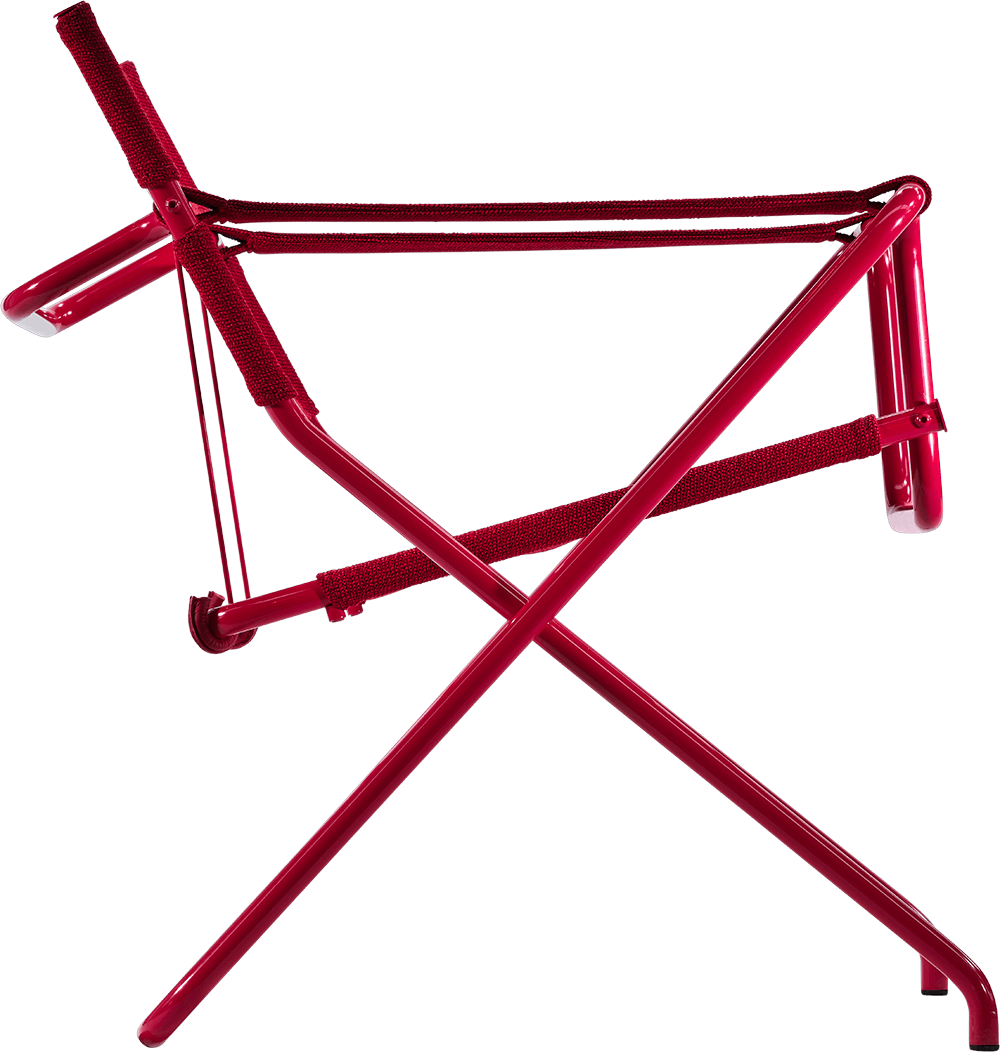

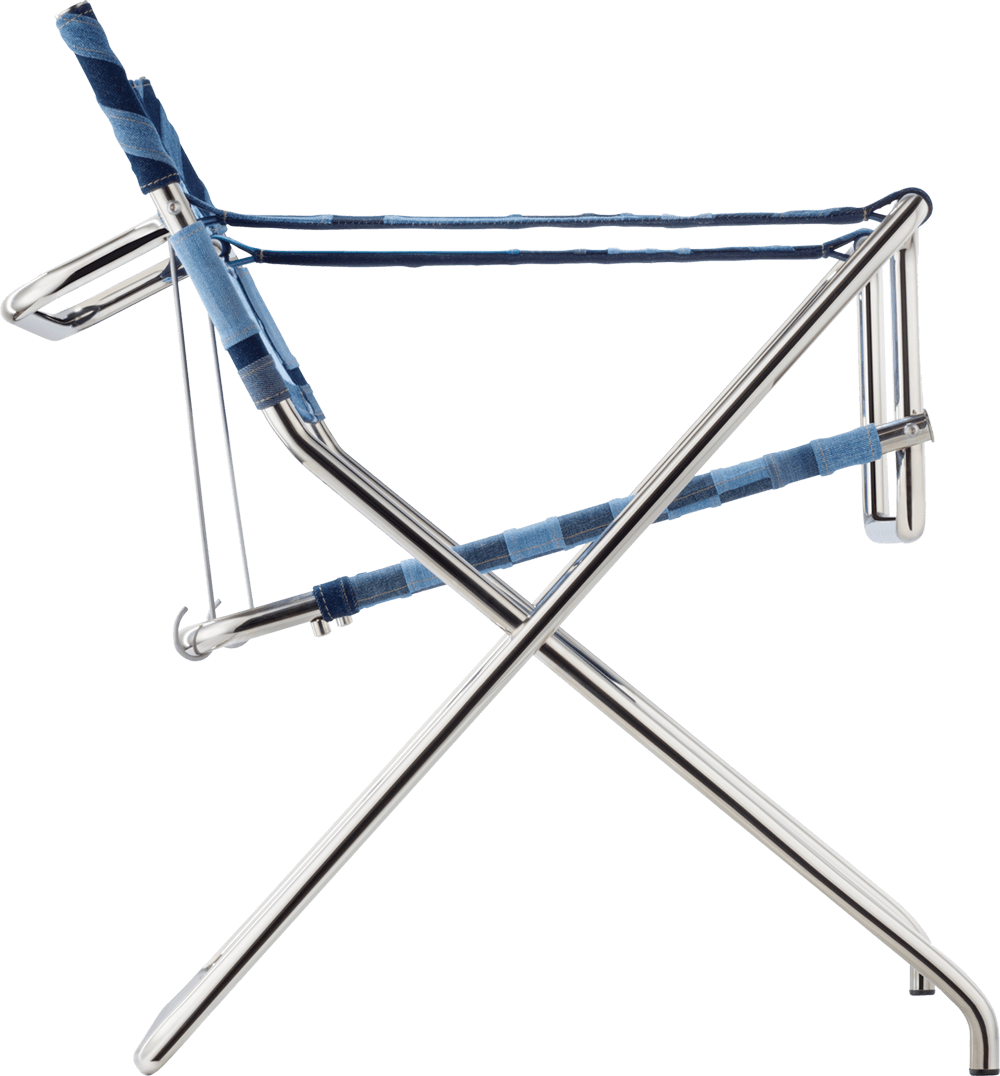

Among all of Marcel Breuer’s iconic designs, the D40 from 1928 holds a special place. You could trace its outlines with your eyes closed. An elegant S-curve describing a slight diagonal in the upper third – the backrest. A dynamic experience that exudes calm. Because every curve of the steel tube is finely balanced. Arch-curve-countercurve: a construction that harmoniously reconciles all contrasts. This was possible due to bent tubular steel – a technology that revolutionised furniture design. And made it lighter than ever before. Marcel Breuer wrote in 1924: “A chair…should not be horizontal/vertical, nor should it be expressionist, nor constructivist,” it should be a “good chair, then it will match a good table.”

+ read more

- einklappen

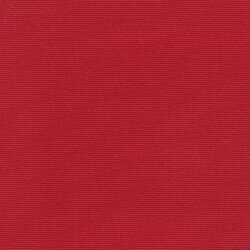

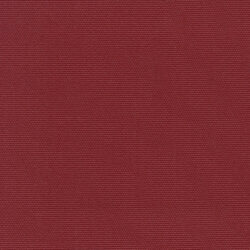

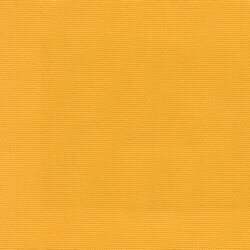

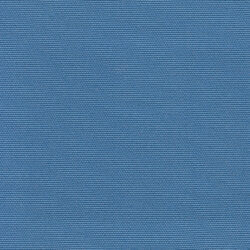

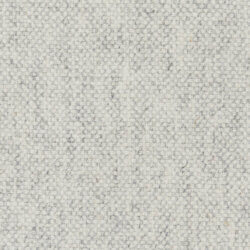

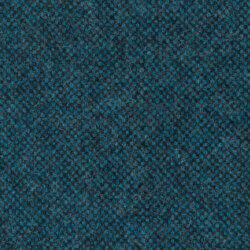

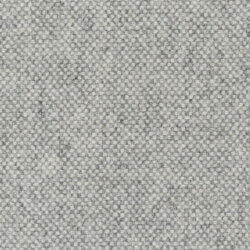

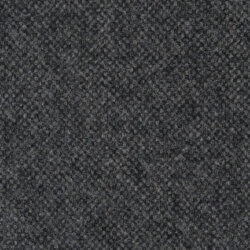

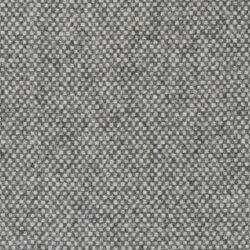

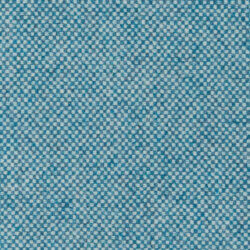

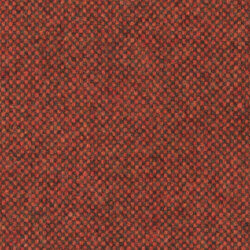

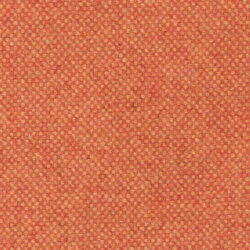

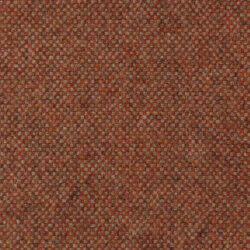

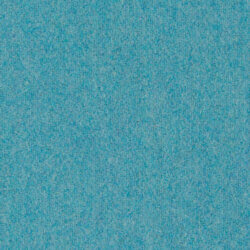

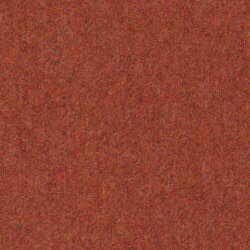

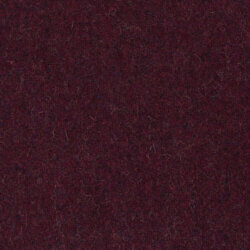

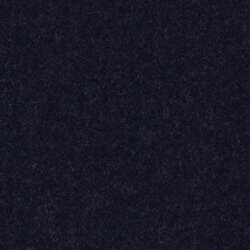

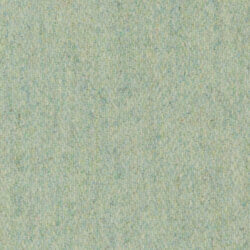

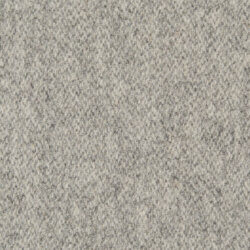

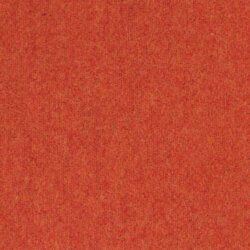

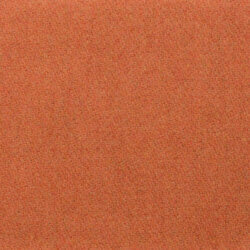

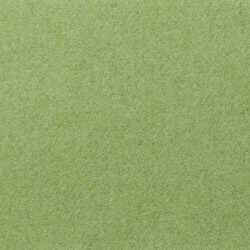

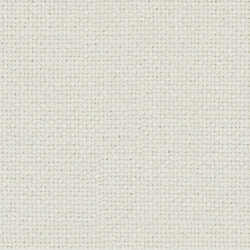

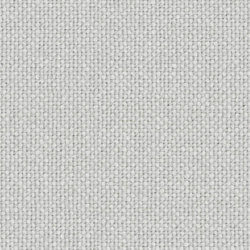

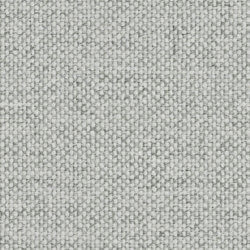

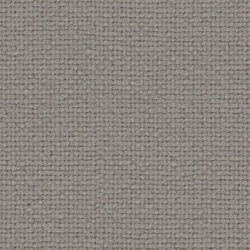

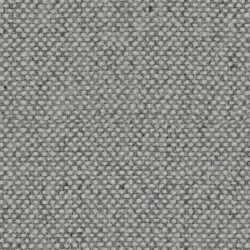

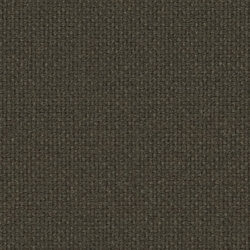

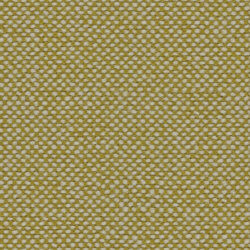

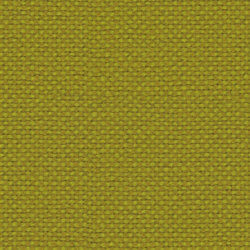

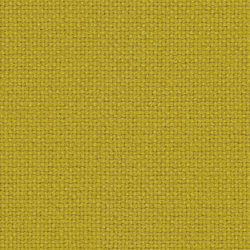

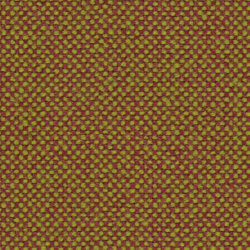

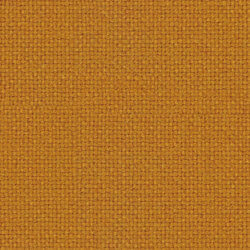

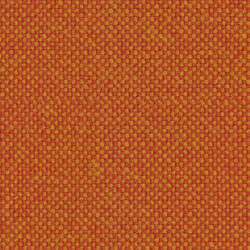

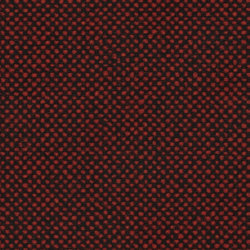

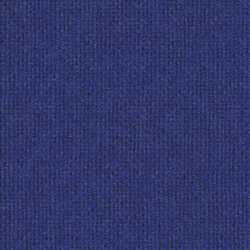

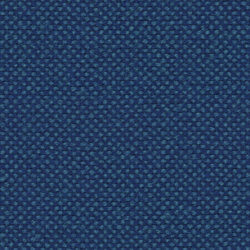

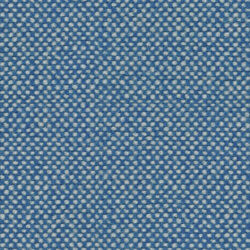

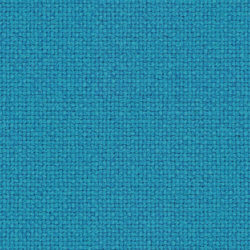

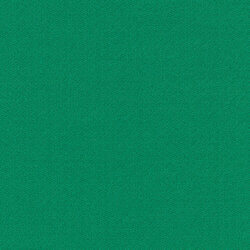

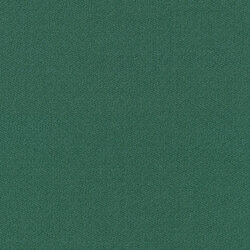

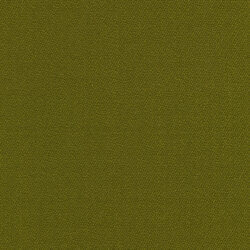

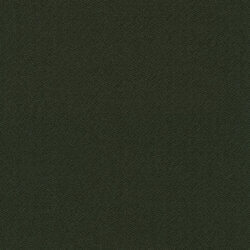

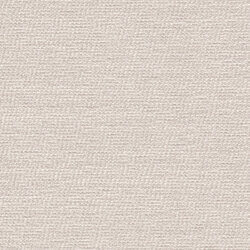

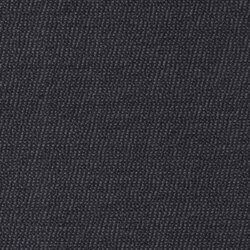

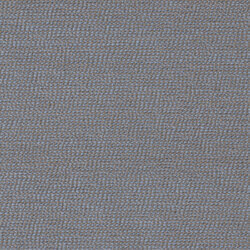

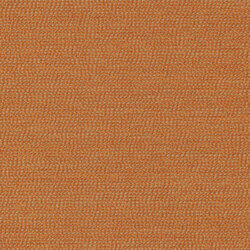

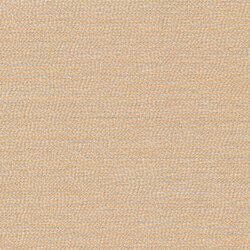

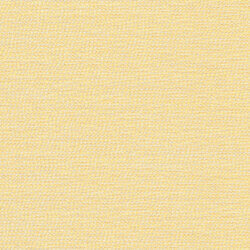

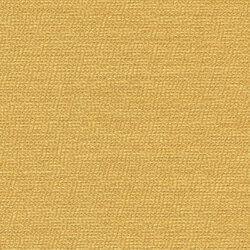

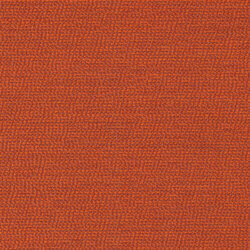

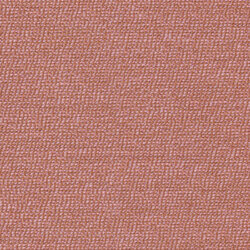

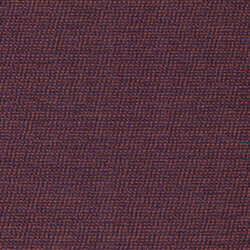

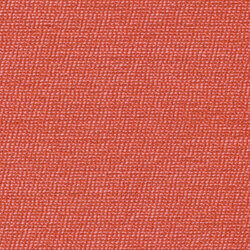

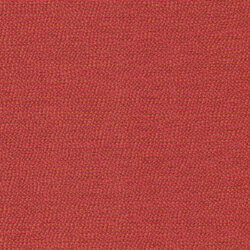

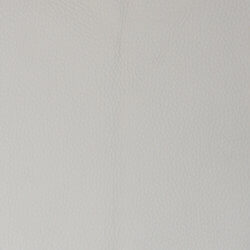

But people did want to know exactly what a good chair is. Because one thing was certain: Breuer was unwilling to compromise. Hence, the workmanship also had to be of the finest quality. The fabric straps were specially created in Grete Reichert’s own weaving workshop out of multiple twisted cotton threads treated with paraffin for better stability and dirt-resistance and known as “eisengarn” (iron yarn). Even today, the seat and back straps are made of a particularly hard-wearing material. This allows you to feel all the benefits of a “good chair”.

Perfection of construction and detail. Of course, the first thing we associate with Bauhaus master Marcel Breuer is one material: tubular steel. And one principle: the cantilever chair, which sparked modern furniture design. “Humankind was freed from the tethers of rigid sitting to enjoy the freedom of the floating seat. The cantilever chair was a symbol of its time.” But this does not really do justice to Marcel Lajos (“Lajkó”) Breuer (1902-1981). What he really pursued was research into the essence of objects: what should, what can a modern piece of furniture do today, was the Bauhaus question.

+ read more

- einklappen

In 1925, Breuer became head of the furniture workshop in Dessau as a “junior master”. The year before, he had already postulated his definition of contemporary furniture. Although he attached great importance to details, Breuer favoured the precision of thinking over formal aspects. “There is the perfection of construction and detail, along with and in contrast to simplicity and generosity in form and use,” he wrote in an essay outlining his philosophy.

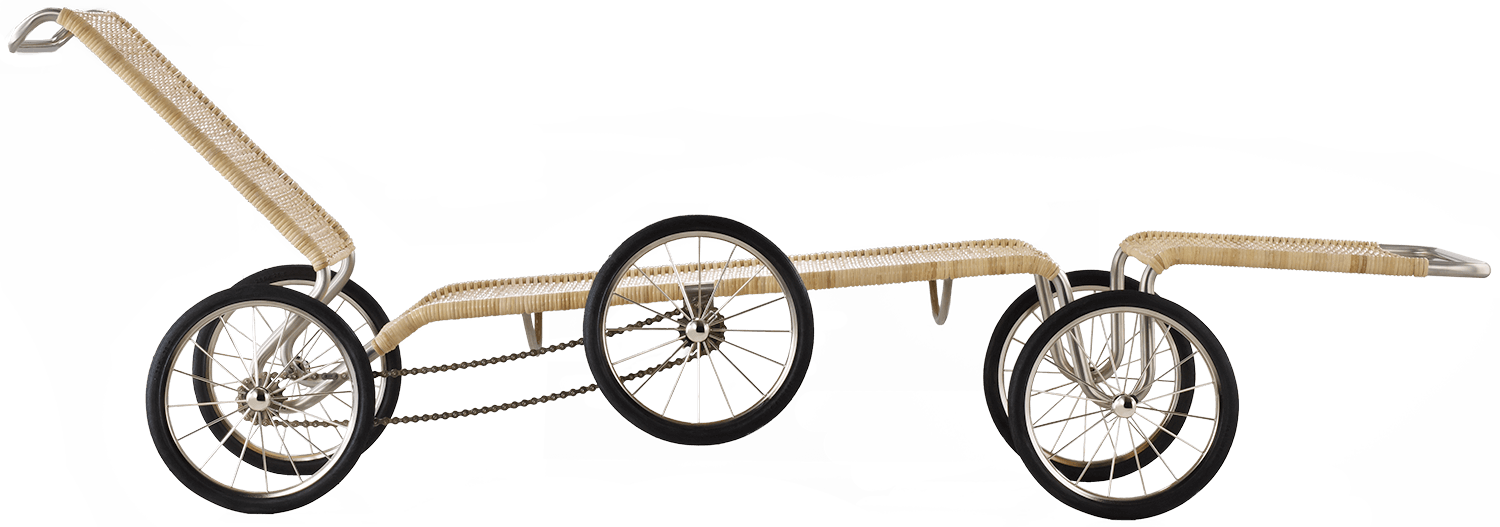

His role in popularising tubular steel for furniture design may also be due to his being one of the first to realise how dynamic our lives had become, demanding equally light and flexible solutions. The cycling enthusiast also embraced the latest trends in architecture, industry and design for a new zeitgeist. “I have specifically chosen metal for these pieces of furniture to achieve the characteristics of modern spatial elements,” explained Breuer. “The heavy upholstery of a comfortable armchair has been replaced by tightly stretched fabric surfaces and a few lightweight springy cylindrical brackets.”

In addition, the construction was no longer hidden, but flashing chrome became a visible part of the design. Cantilever chairs were bolted, not welded, functions stacked and colour-coded. The result was a dematerialised floating appearance and a new spirit of space. The cantilever chair meant a liberation from the thousand-year-old model of rigid throne-like sitting. It was the implementation of the functional, kinetic and constructive counter-principle. This kinetic line, the dawn of the modern era, can still be traced to the young Bauhaus designers today.

Products Marcel Breuer