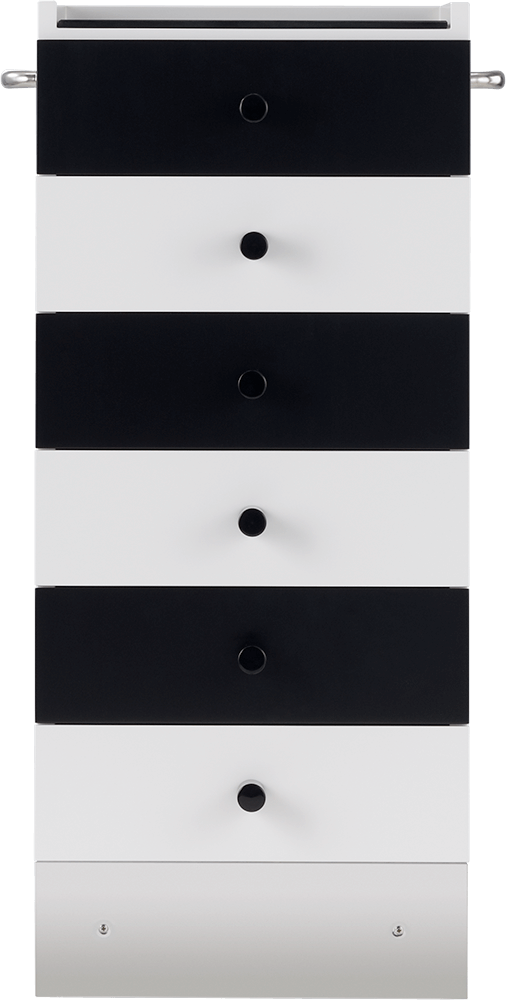

S41

The instinct of perfection

A design as simple as it is comprehensible: for his S41 chest of drawers (designed in 1924/27) Marcel Breuer stacked six drawer units, marking them alternately in contrasting colours: black and white. In turn, the black lacquered handles either merge with the equally black front or form a stark contrast. This creates a rhythm, which comes to rest again with the black glass top. It features a useful detail: the slightly raised edges of this “attica” keeps pens from rolling off the top.

+ read more

- einklappen

With its strong architectural design, this chest of drawers clearly takes centre stage. Two handles on the sides strike a balance with its perfect shape, as if to hint that, from now on, chests of drawers should not remain in one spot but can be easily moved on castors. “God knows, I am all for informal living and for architecture in support of and as a background for this,” Breuer wrote in an essay, adding mischievously: “but we cannot evade the instinct of perfection – a truly human instinct.”

Breuer used these small chests of drawers with their vibrant black and white contrasts in all his interiors at Bauhaus Weimar from 1924 to 1926. Expressive basics that were always built according to human proportions with a highly aesthetic effect owing to their ingenuity. They have retained their signature handles until this very day.

The S41E version of the S41 chest of drawers is even lighter and more flexible, with a stainless steel body evoking the Bauhaus’ innovative use of tubular steel.

S 41: True to the original and with license.

How can you recognize the original Bauhaus reeditions from Tecta? The Bauhaus Archive in Berlin only approves true-to-work and licensed reeditions of the original Bauhaus models. These are marked with Oskar Schlemmer’s signet, which he designed for the Weimar State Bauhaus in 1922. Even today, our Bauhaus models are based exactly on the proportions of the originals.

Perfection of construction and detail. Of course, the first thing we associate with Bauhaus master Marcel Breuer is one material: tubular steel. And one principle: the cantilever chair, which sparked modern furniture design. “Humankind was freed from the tethers of rigid sitting to enjoy the freedom of the floating seat. The cantilever chair was a symbol of its time.” But this does not really do justice to Marcel Lajos (“Lajkó”) Breuer (1902-1981). What he really pursued was research into the essence of objects: what should, what can a modern piece of furniture do today, was the Bauhaus question.

+ read more

- einklappen

In 1925, Breuer became head of the furniture workshop in Dessau as a “junior master”. The year before, he had already postulated his definition of contemporary furniture. Although he attached great importance to details, Breuer favoured the precision of thinking over formal aspects. “There is the perfection of construction and detail, along with and in contrast to simplicity and generosity in form and use,” he wrote in an essay outlining his philosophy.

His role in popularising tubular steel for furniture design may also be due to his being one of the first to realise how dynamic our lives had become, demanding equally light and flexible solutions. The cycling enthusiast also embraced the latest trends in architecture, industry and design for a new zeitgeist. “I have specifically chosen metal for these pieces of furniture to achieve the characteristics of modern spatial elements,” explained Breuer. “The heavy upholstery of a comfortable armchair has been replaced by tightly stretched fabric surfaces and a few lightweight springy cylindrical brackets.”

In addition, the construction was no longer hidden, but flashing chrome became a visible part of the design. Cantilever chairs were bolted, not welded, functions stacked and colour-coded. The result was a dematerialised floating appearance and a new spirit of space. The cantilever chair meant a liberation from the thousand-year-old model of rigid throne-like sitting. It was the implementation of the functional, kinetic and constructive counter-principle. This kinetic line, the dawn of the modern era, can still be traced to the young Bauhaus designers today.