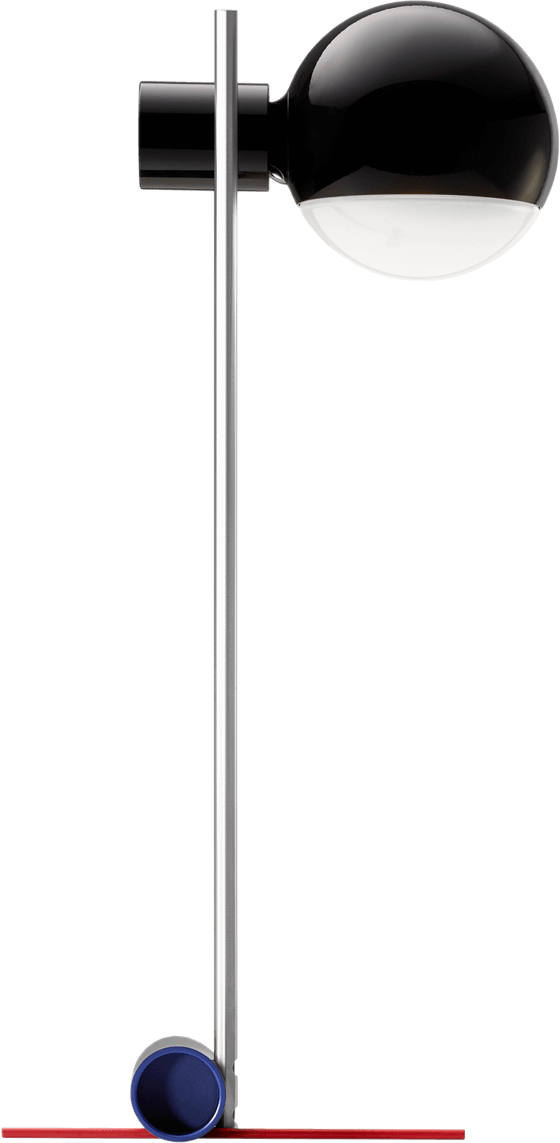

L25N

Rietveld Tafellampje

Limited Edition

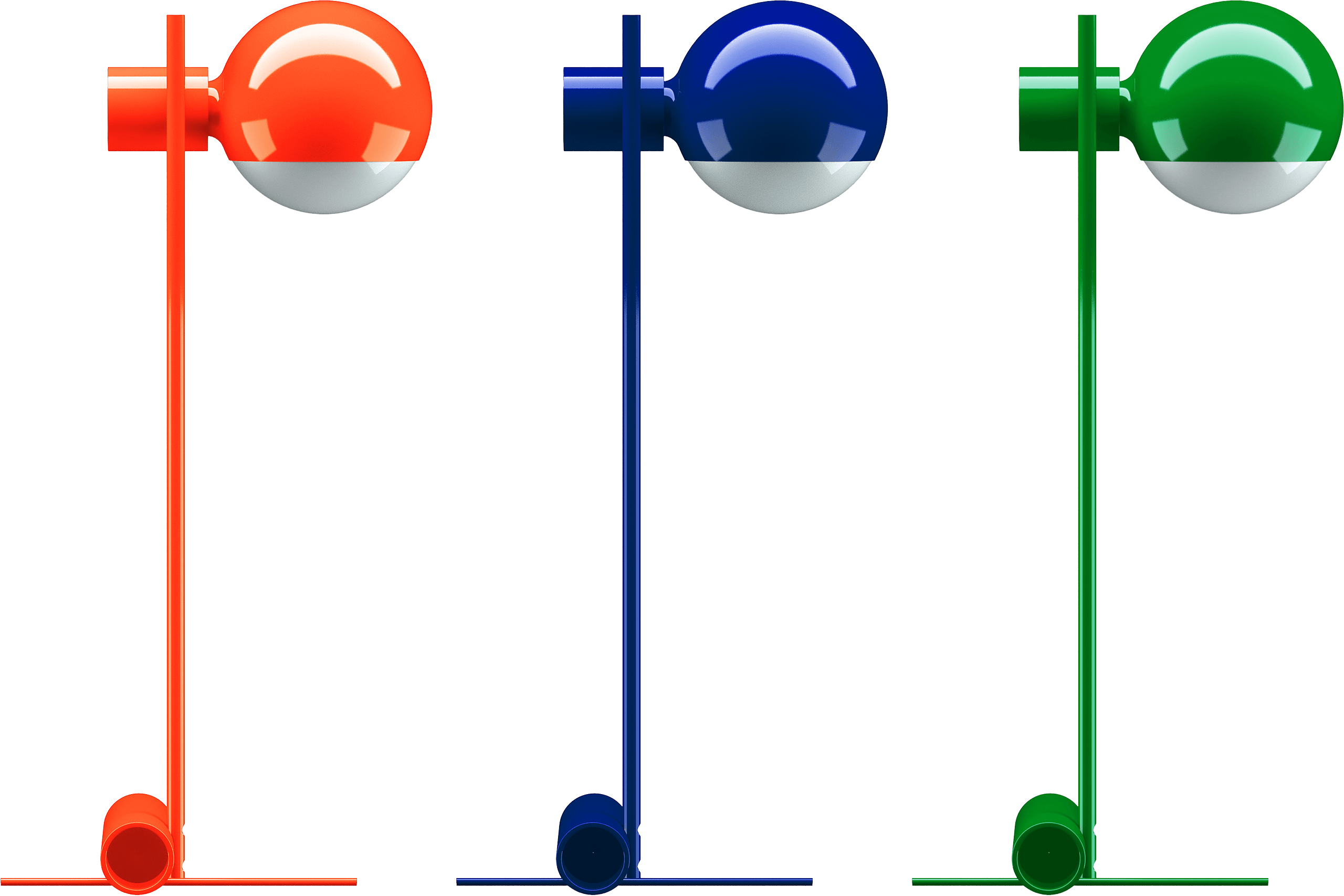

This is the second reinterpretation of the L25, a first edition limited to 20 pieces each: in pastel yellow, pastel green and pastel pink. Rietveld and his contemporaries in the De Stijl movement were very bold in their use of colour at the time. The new edition picks up on this courage. And makes a light, elegant, almost floating statement – as a deliberate counterpoint to the strict and constructed design language of the luminaire.

+ read more

- einklappen

With the almost 40 centimetre high table lamp, which Rietveld designed in 1925, he transformed the horizontal and vertical into a captivating, small object whose filigree construction merges into a single unit thanks to the new colours. The paintwork is complex: the lamp has to be painted around five times to achieve its colour effect. This is what creates the soft look that makes it appear more sculptural and less technical. It was a challenge for Tecta to translate the design into contemporary LED technology. Today, the result is a luminaire that is as technically sophisticated as if it had been designed for modern light sources from the outset.

„The maker of things – sometimes of magical things“

(Peter Smithson, 1965)

Carefully reflecting on my personal relationship with Rietveld and Haus Schröder, my first thought was that there should not be too much talk; because what I admired most about Rietveld was his calm. His seemed to me the only pattern of behavior for a true architect.” Rietveld touched only small things, each given its own life, enriching the city (usually his own hometown), for its own ordinary good. Except that sometimes it became a world event that touched everyone. Never the assessor, the councilor, the writer of introductory remarks, the knowing expert at government commissions. Simply a builder and furniture maker. Simply a Baumann and furniture maker?

+ read more

- einklappen

Then you see why the worlds are built. Because it is undeniable that the red and blue chair and the Schröder house are magical objects, and that is what first attracted me to Rietveld. The work of members of the De Stijl group is usually wonderful, and a few De Stijl objects are magical things. Theo van Doesburg’s never are. Mondrians often, Van der Lecks often – but children’s magic, not adult magic. It is not for me here to try and explain how the magic came. I cannot believe that anyone could be intentionally magical, but the mysticism of the early De Stijl movement – theosophy (even Le Corbusier quotes Krishna Murti in the “Ville Radieuse”) – cannot have absolutely nothing to do with it. However, there is no doubt that the De Stijl movement renewed the life forces of architecture and painting at that time; and we can still feel that now, as indeed one can feel the magic of an earlier time in Segesta – that kind of magic lasts a long time. The magic is in the things themselves and it is not present in their photographs. De Stijl objects meant after the first war what Pollock and Eames meant to my generation after the second war – they enabled the art life to begin again. P.S., March 1965

And people will say the same things about the Eames that they say about Rietveld: “What’s so great about what they did? Just a house and a few chairs”. A.S., published in Building and Living, July 1965