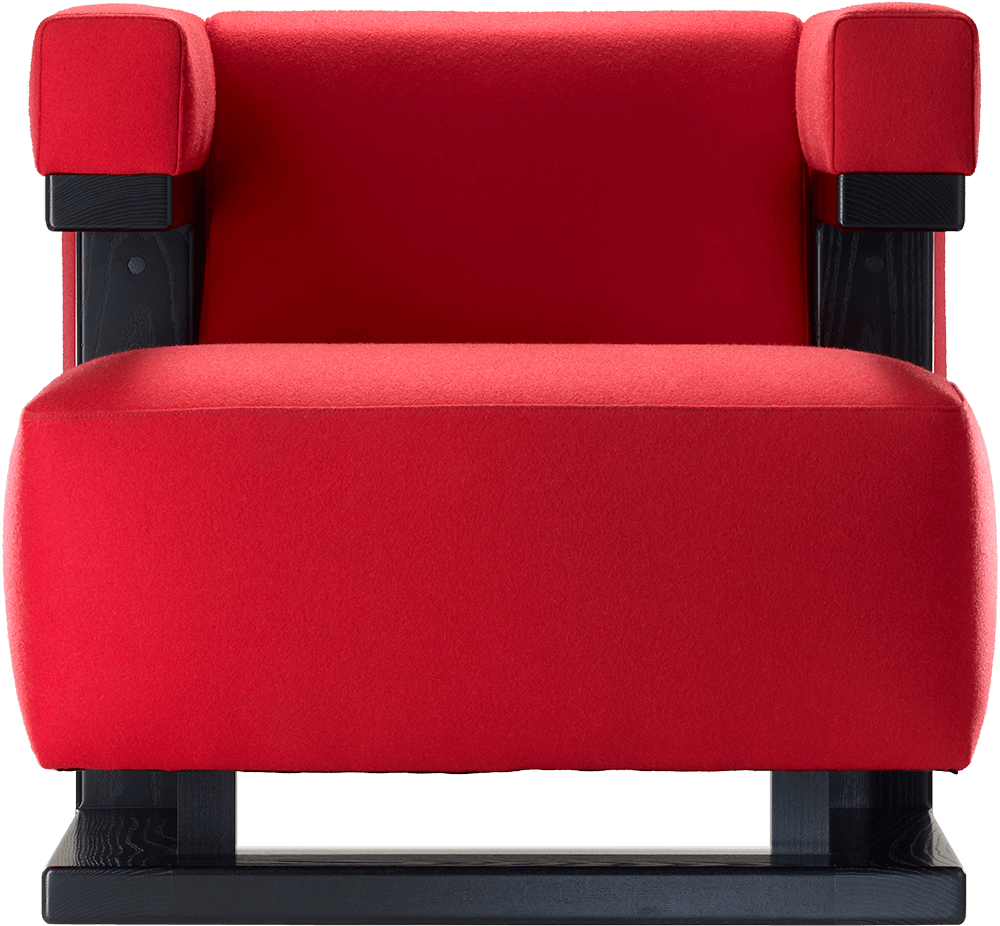

F51

Ground-breaking cube

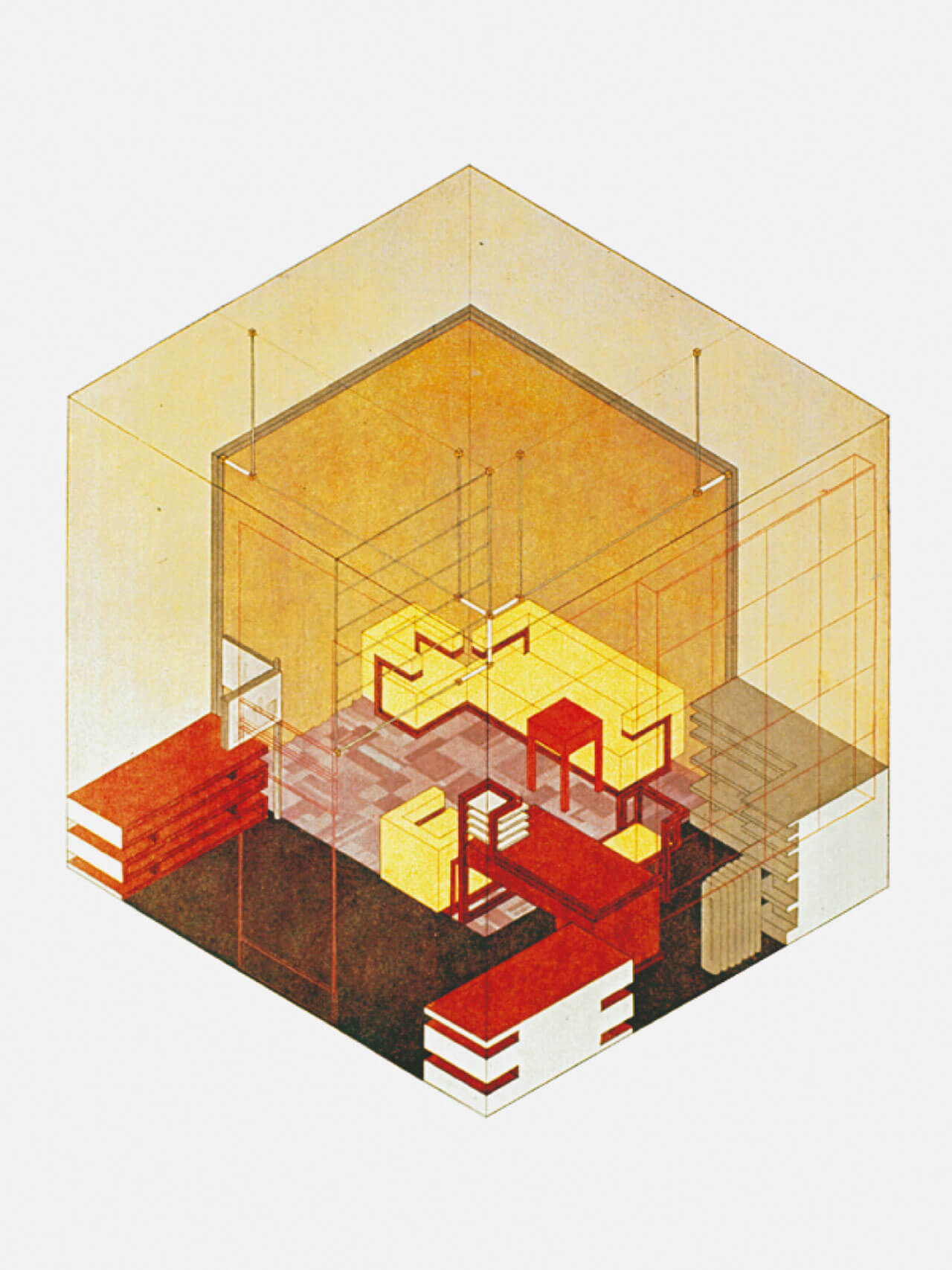

We are in the arcanum of modernism. The F51 (1920) is not just any armchair, it is the iconic armchair for the director’s room in the Weimar Bauhaus. Walter Gropius had already injected his modernist dynamic into the building and created a small holistic work of art, encompassing interiors and furniture, tapestry and ceiling lamp. Nothing is randomly chosen and everything is connected. If you study the isometric layout of the director’s room you can see the furniture as part of a three-dimensional coordinate system.

+ weiterlesen

- einklappen

All major designers, including Mart Stam, have walked through this central room of the Bauhaus in Weimar. Consciously or unconsciously, they were already influenced by the overarching ideas of the F51 armchair. Its protruding armrests can be seen as a precursor of Mart Stam’s chairs without back legs and anticipate Marcel Breuer’s stool on runners (1925).

“The first cantilever chair concept is from Walter Gropius, the first cantilever armrest architecture from El Lissitzky,” says Tecta’s Axel Bruchhäuser. Walter Gropius’ own thoughts: The goal of modern architecture is “to defy gravity and overcome the earth’s inertia in impression and appearance.” This later became the intellectual root of the cantilever principle and the creed of the collection in Tecta’s Cantilever Chair Museum in Lauenförde.

Despite its cubic form, the chair has an almost human appearance with its heavy but floating upholstery and simple frame. With the F51 Gropius has made a piece of space around us tangible and given it a geometric shape. It seems as if the architect had intermeshed two C-shaped elements in such a way that they continue to convey suspense. The projecting frame lifts the back of the seat and armrest upholstery away from the floor. Calm and dynamism – the armchair radiates both simultaneously and thus points to the architect’s future-forward design approach, which radically questioned all things traditional.

In 1926 Gropius wrote emphatically in his “Principles of Bauhaus Production”: “It is only through constant contact with constantly evolving techniques, with the discovery of new materials and with new ways of putting things together that the creative individual can learn to bring the design of objects into a living relationship with tradition.” The intricately crafted F51 armchair is a case in point. Existing elements are reinterpreted and the construction, the “crafted” elements are openly revealed.