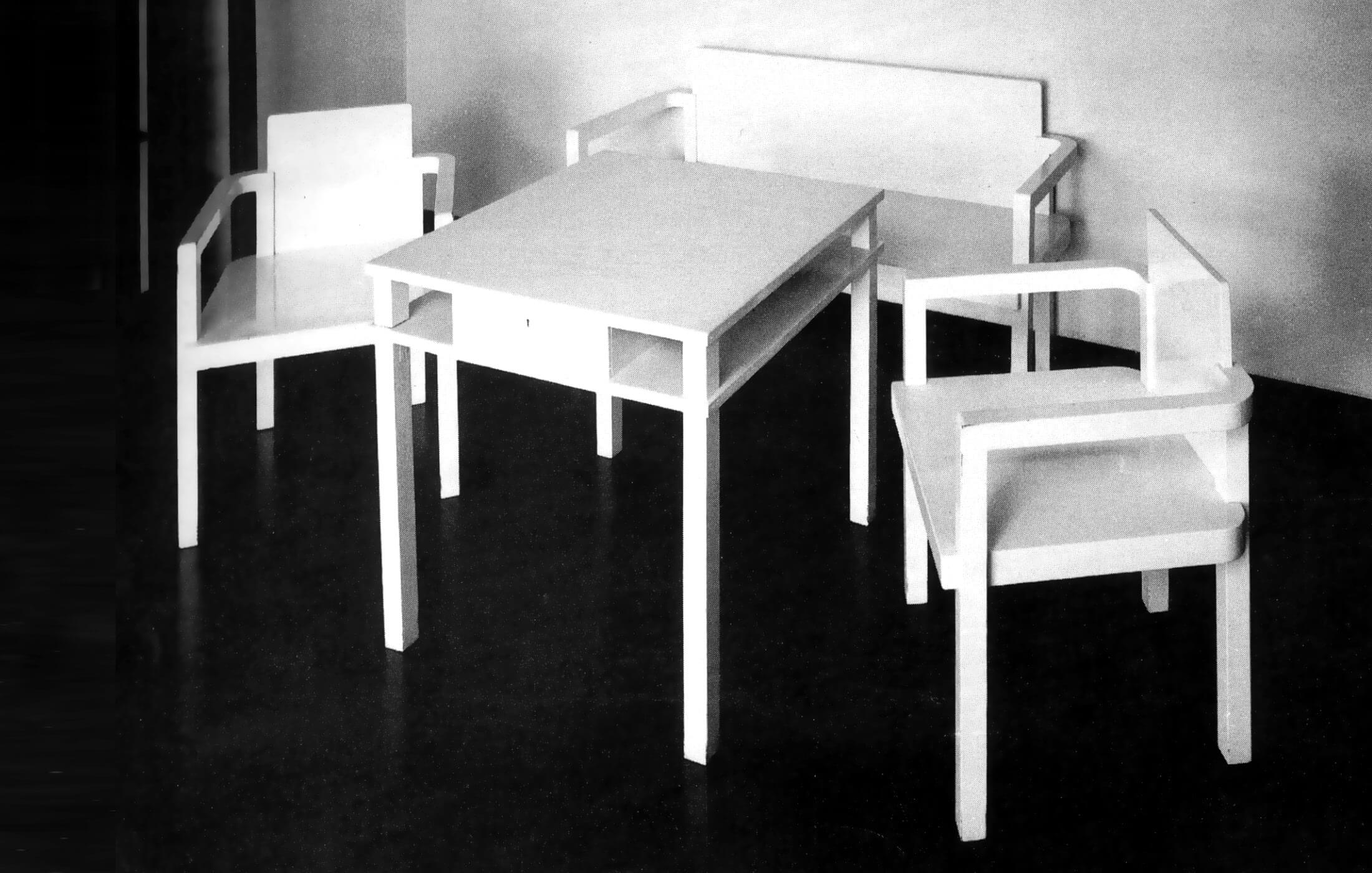

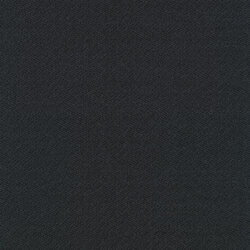

D51-3

Clear rhythm for the room

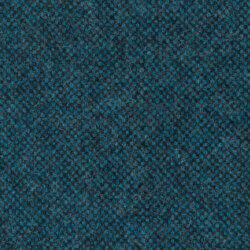

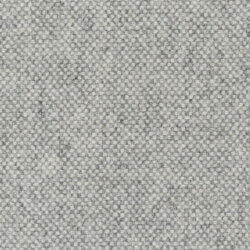

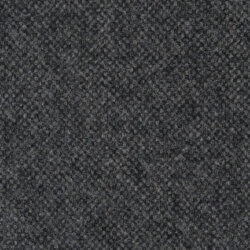

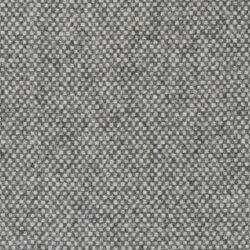

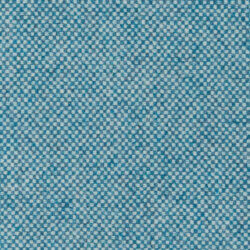

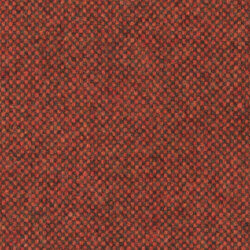

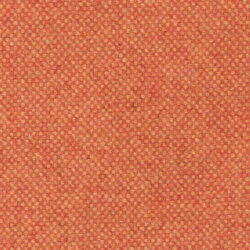

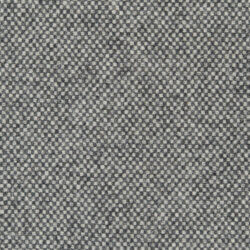

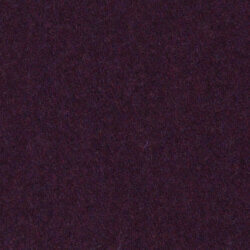

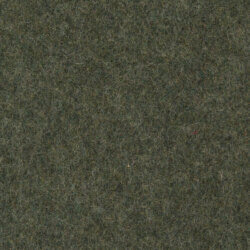

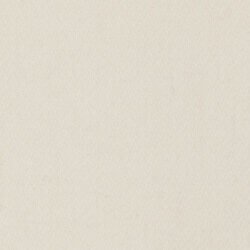

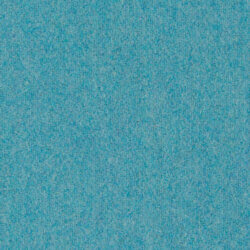

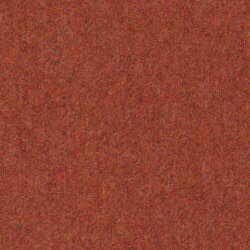

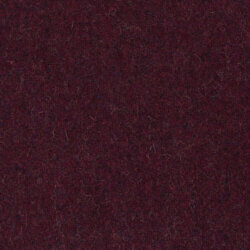

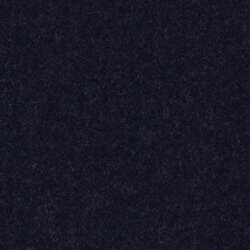

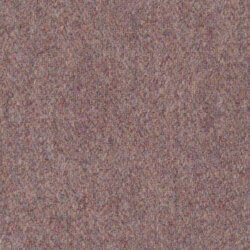

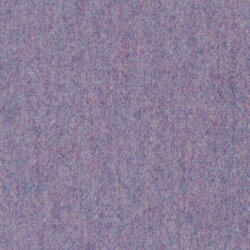

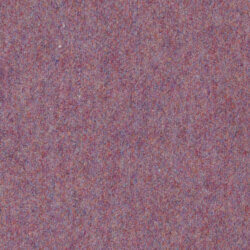

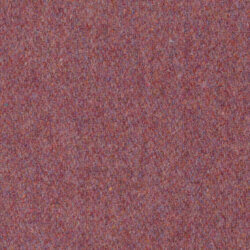

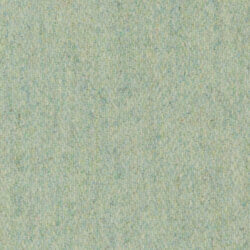

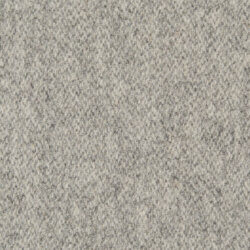

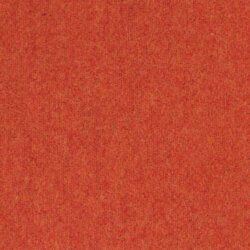

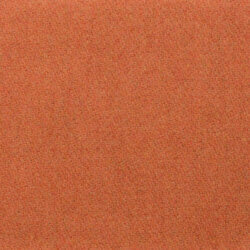

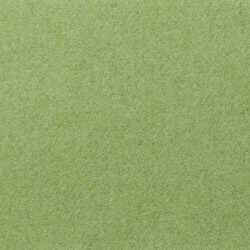

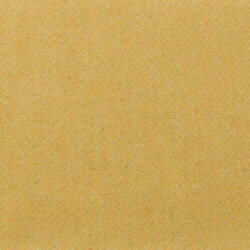

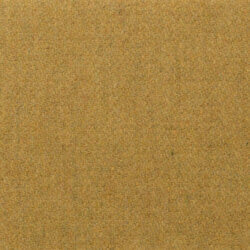

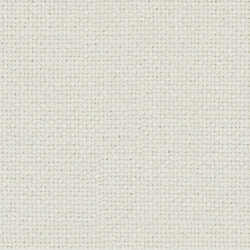

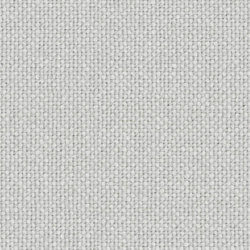

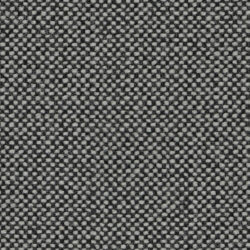

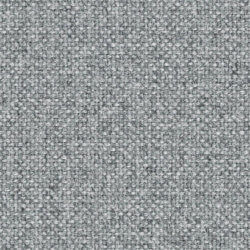

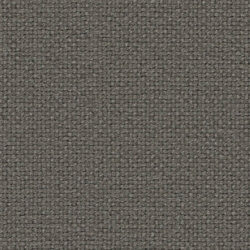

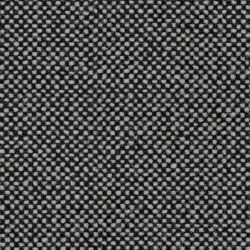

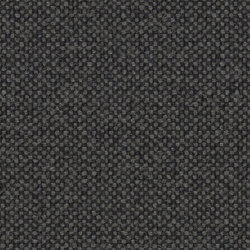

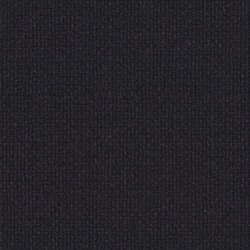

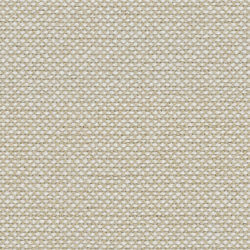

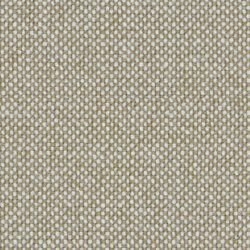

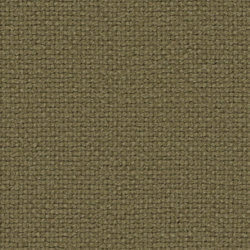

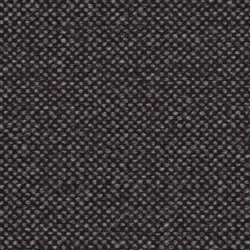

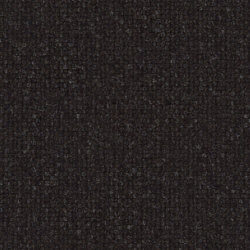

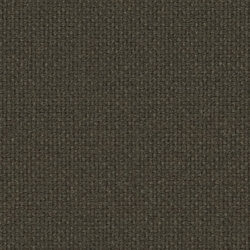

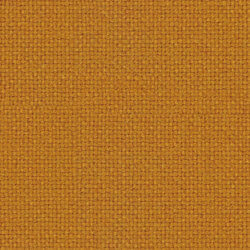

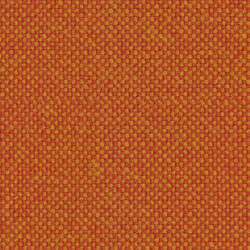

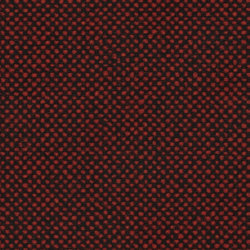

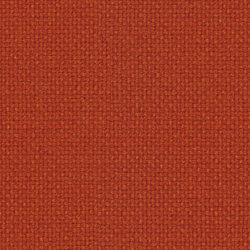

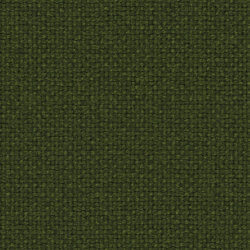

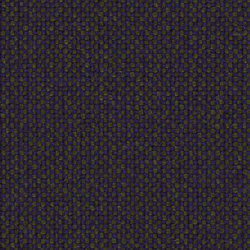

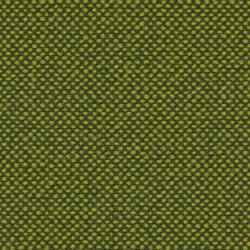

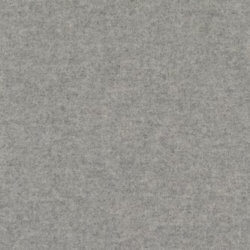

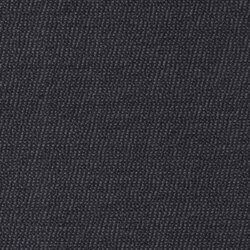

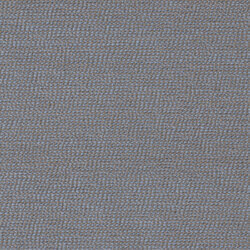

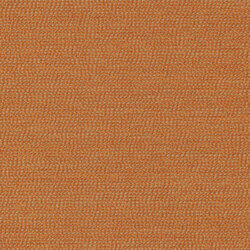

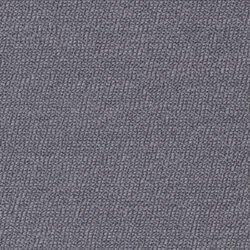

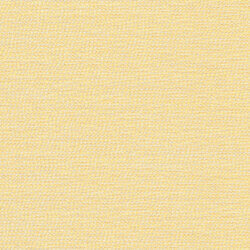

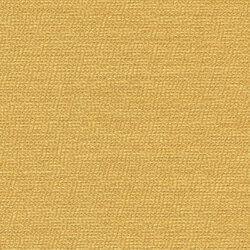

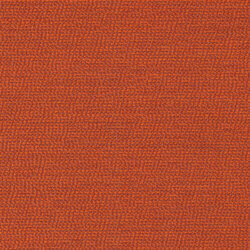

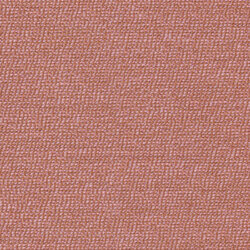

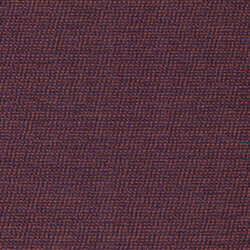

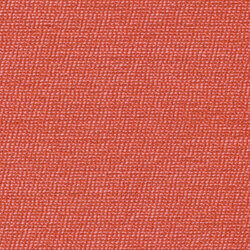

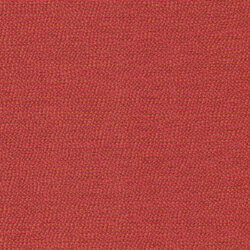

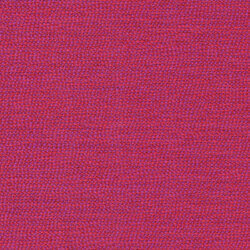

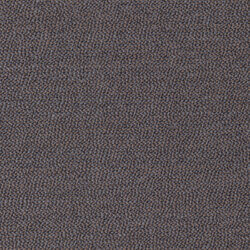

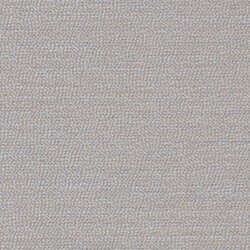

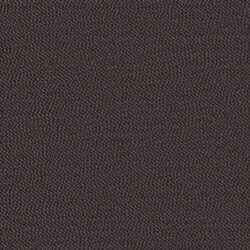

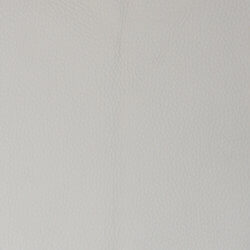

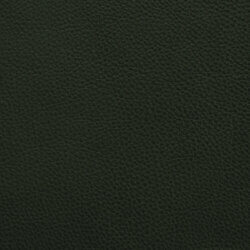

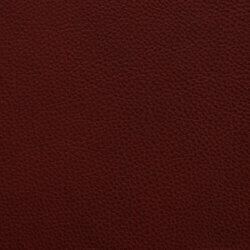

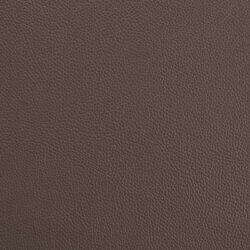

Simple elegance is the hallmark of the two-seater D51-2 sofa from 1922/23. One could also say: a virtually uncompromising attitude. Streamlined to perfection, it is geared to no other purpose than to seating two or three people. The details make the design – rounded corners casually encompass the sitter, the legs are set astride giving them an almost human appearance. The individual elements seem to be lined up as if by a ruler. The sofa and its backrest create a clear rhythm in the room, which is amplified by the upholstery fabrics. Instead of sinking into luxuriant cushions, you are borne on flat upholstery elements that could be floating parts of the kind favoured by constructivist artists. Gropius not only knew how to express the creative upheaval of the era in design but also created a conceptual framework for it.

+ read more

- einklappen

Comprising a chair and two-seater sofa, the collection was intended for the vestibule of the Fagus factory, where Gropius pushed wide open the door to modernity. “In his eternal curiosity man learned to dissect his world with the scalpel of the scientist, and in the process has lost his balance and his sense of unity,” believed the architect, and created an integrative architectural icon.

As it happened, over the course of time, this story was interwoven with Tecta’s story. Axel Bruchhäuser, partner of the company since 1972 and an important witness of the Bauhaus generation, recalls: “We sat in the foyer on chairs by Walter Gropius, of which the owners knew nothing at all. During my research I discovered a drawing of the chairs and got in touch with Ise Gropius in the USA for the first time. We asked her if we could produce this chair under licence and her reply was an enthusiastic: yes, that would be possible.”

Later, Tecta developed a three-seater counterpart, the D 51-3, to complement the two-seater sofa. It appears as if reflections on the topic of sitting and resting have become an integral part of the design. The long straight line wants to be paired with a matching vertical. The back and armrests lend the furniture stability and boundaries. It is an old rule among designers that elegance can be achieved by stretching the proportions. The furniture line was extended, creating a perfect interaction between aesthetics and function. This furniture also bears the Oskar Schlemmer label for faithful reeditions.

Founder and thinker of the Bauhaus philosophy. The architect and founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius (1883-1969), mocked traditional architecture as “salon art”. He descended from a family of great builders: his great uncle was Martin Gropius. Walter Gropius abandoned his architectural studies and initially joined the office of Peter Behrens – as had, incidentally, Adolf Meyer, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. A short time later, Gropius founded what we now call modernism – a major break from and with the conventions of the past.

+ read more

- einklappen

One key feature was that he did not reject the principles of the industrial age – standardisation and prototypes – but made them productive tools for his work. “A resolute affirmation of the living environment of machines and vehicles,” wrote the Bauhaus director in 1926, who believed that “the creation of standard types for all practical commodities of everyday use is a social necessity.”

This spirit not only gave rise to the Fagus factory as an icon of modern architecture and the Dessau Bauhaus, but also laid the foundations of what is still a driving force for us today. “The objective of creating a set of standard prototypes which meet all the demands of economy, technology, and form, requires the selection of the best, most versatile, and most thoroughly educated men who are well grounded in workshop experience and who are imbued with an exact knowledge of the design elements of form and mechanics and their underlying laws.”

By founding the Bauhaus, Gropius launched a new school of thought, opposing the traditional architecture of which he was so critical. In 1919 Gropius was appointed director of the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar, Thuringia, and named the new school “State Bauhaus Weimar”.

Gropius’ driving vision was not only to construct a “building of the future” and a holistic work of art, but also the highly modern approach of maintaining the distinction between apprentice and master while intermeshing the two teachings in a novel manner. To work across the disciplines, with an interdisciplinary approach in the spirit of research and experimentation.

Gropius also knew how to translate architectural concepts into furniture design, exemplified by his unique penetration of volume and linearity that characterises many of his works. Walter Gropius directed the Bauhaus until its closure in 1933, emigrated to England in 1934 and to Cambridge, USA, in 1937 to teach as professor of architecture at Harvard University.